[Audio Guide]

This work, Does the Universe Turn to Contraction?, was inspired by cosmic inflation, a cosmological theory proposed in the 1980s in which smaller cosmic units emerge one after another within the sphere of the universe as a whole. Nomura captures in three dimensions the theoretical moment when the ever-expanding mass of the universe reaches its limit and “turns to contraction” due to its own gravity, in other words the moment when the vast universe begins shrinking back into a point once more, revealing a dramatic cosmic modality as seen from the exterior of space-time. With its rounded, comical shape reminiscent of a mushroom and its striking structure of repeating identical shapes of different sizes enclosed in glass, this appears to be a dainty little piece, but it is also a work of magnificent scale that inquires into the expansion and contraction of the universe and the beginning and end of space-time, which lie beyond the realm of the visible.

[Audio Guide]

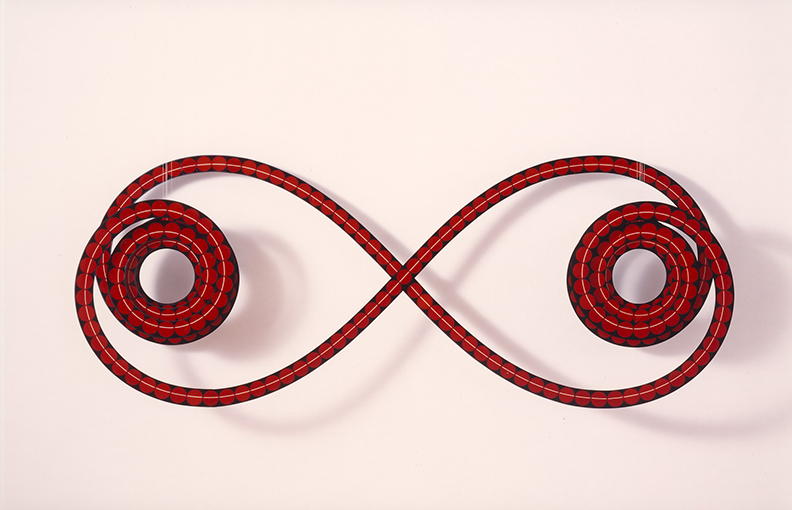

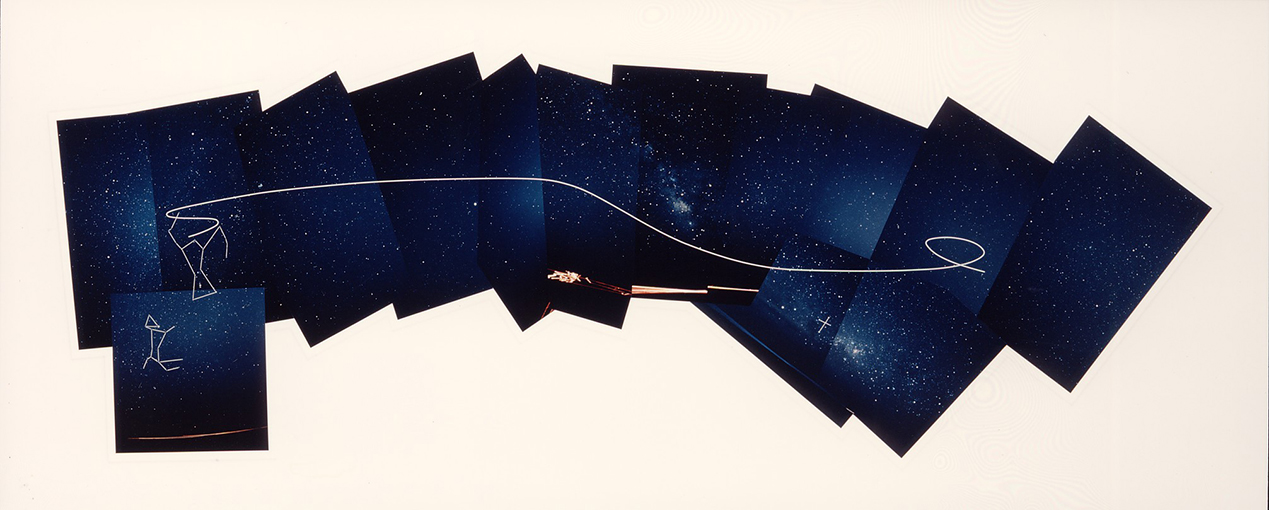

Legible as a symbol of infinity, this work equally contains a sense of suspension and of a strange existence. The interconnected red circles are photographs of the sun taken from sunrise to sunset using a fish-eye lens. The movements of the sun over the course of 365 days as viewed when looking up from the equator has produced this unique shape of two interlocking helixes. The lack of uniformity between both sides is due to the center of the helix on the left-hand side representing the summer solstice, and that of the right-hand side the winter solstice. The layering of Nomura’s photographs in The Sun on the Equator shows not only the movements of the sun over the course of a year, but the work also visualizes in one glance the asymmetry of an universe that we assume to be perfectly ordered. Just as a sculptor may carve out their sculpture from within a piece of wood or stone, Nomura carves out the divine symbols hidden in the sky through his photographs.

[Audio Guide]

aiueo

[Audio Guide]

How was the universe brought into being? This question has stirred our imagination since time immemorial. Taking this grand question from ancient times as its title, this work uses blown glass to join together a variety of different mushrooms in a way that is both beautiful and amusing. Nomura began producing works about the universe from the 1980s, and in 1987 started a series that used blown glass. By creating an amalgamation of a shape that proliferates—such as a mushroom—it seems as though the artist is giving concrete form to his image of the universe. Nomura is giving solidity to the descendant galaxies that spring from parent galaxies, which continue to generate plural galaxies without end.

[Audio Guide]

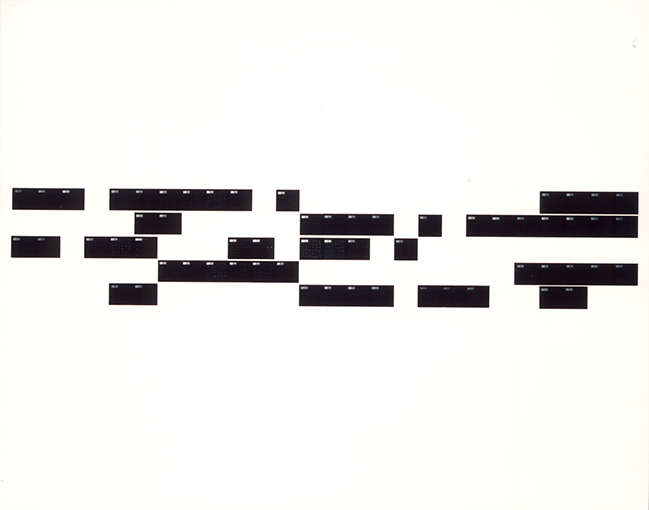

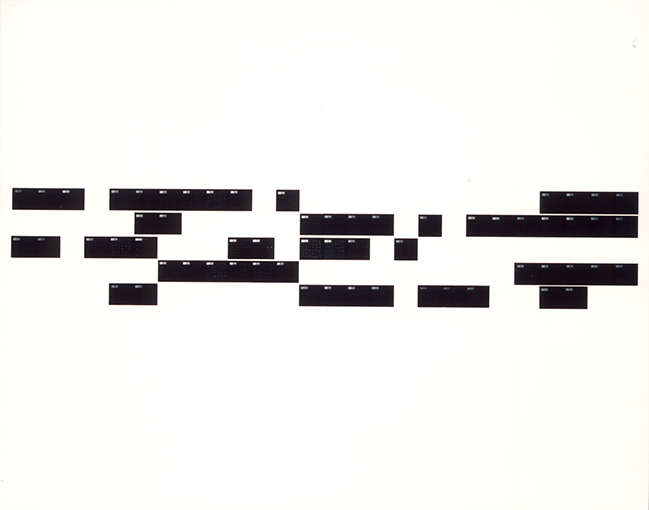

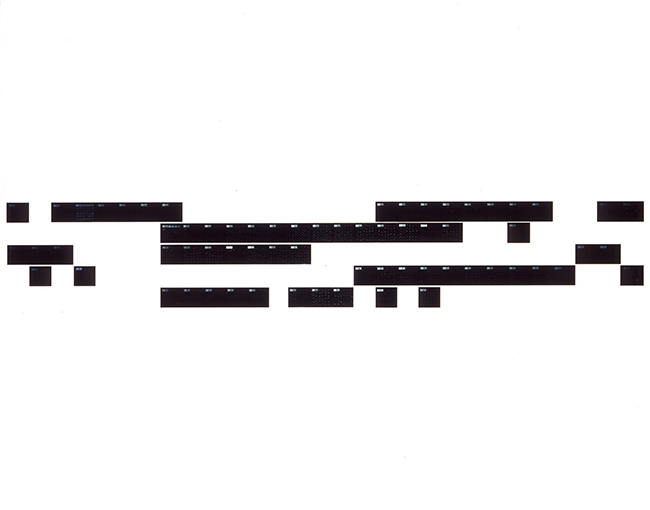

Nomura came up with the idea for the ‘moon’ score series on his commute to work, when he looked up and saw the moon passing through electricity lines and pylons as if it were a musical note. This work is composed of 61 photographs of the moon taken during February of each year from 1980 to 1984. He used 35mm film onto which a staff notation had been copied. These were then imposed onto each of the images of the moon as it was photographed each day (34 shots) and reproductions of calendars from the newspaper (2 shots). Temporally, the years progress from top to bottom, with the photographs arranged from left to right according to the day of the month. The blank spaces represent days when the artist could not take any photographs. As he was photographing with a handheld camera, the position of the moon could be changed within the bars of the staff notation, which gives the impression of a sequence of musical notes. The work resembles sheet music, in which the systematic waxing and waning of the moon has been combined with irregular phenomena such as the weather and camera shake in Nomura’s photographs.

How was the universe brought into being? This question has stirred our imagination since time immemorial. Taking this grand question from ancient times as its title, this work uses blown glass to join together a variety of different mushrooms in a way that is both beautiful and amusing. Nomura began producing works about the universe from the 1980s, and in 1987 started a series that used blown glass. By creating an amalgamation of a shape that proliferates—such as a mushroom—it seems as though the artist is giving concrete form to his image of the universe. Nomura is giving solidity to the descendant galaxies that spring from parent galaxies, which continue to generate plural galaxies without end.

[Audio Guide]

This work, Does the Universe Turn to Contraction?, was inspired by cosmic inflation, a cosmological theory proposed in the 1980s in which smaller cosmic units emerge one after another within the sphere of the universe as a whole. Nomura captures in three dimensions the theoretical moment when the ever-expanding mass of the universe reaches its limit and “turns to contraction” due to its own gravity, in other words the moment when the vast universe begins shrinking back into a point once more, revealing a dramatic cosmic modality as seen from the exterior of space-time. With its rounded, comical shape reminiscent of a mushroom and its striking structure of repeating identical shapes of different sizes enclosed in glass, this appears to be a dainty little piece, but it is also a work of magnificent scale that inquires into the expansion and contraction of the universe and the beginning and end of space-time, which lie beyond the realm of the visible.

[Audio Guide]

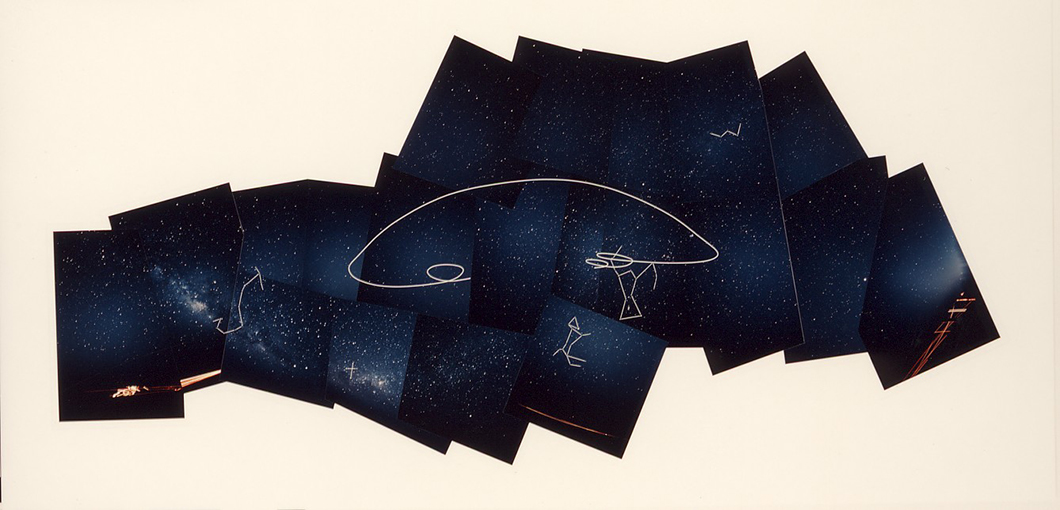

This photobook is composed of a series of stop-motion photographs of everyday scenery, taken by Nomura Hitoshi every month from March 1972 using a 16mm movie camera. These commonplace scenes caught Nomura’s eye, and though they are undated they are documented according to the time of day that they were taken. When we are not focused on any object in particular, our eyes take in our surroundings in a wandering manner. The ‘Brownian motion of eyesight’ mentioned in the title refers to this continually roving, irregular movement of our eyes when we are walking around. Nomura noticed that “Seeing something indistinctly is different from staring at something,” and in this work he was not framing photographs deliberately, but rather, earnestly photographing the scene that lay before the camera. This successive series of photographs were assembled into a 26-volume photobook that uses a camera to visualize the moments we are not usually conscious of.